Festivals involve a lot of labour, sometimes extending over many days beforehand, as in the case of Dipavali and Sarasvati Puja, and a lot of expenditure in money and food resources. Most of the labour devolves on the women folk. Yet they do not seem to grudge it. They always engage themselves in these activities with great enthusiasm. Even people not so well placed do not appear to mind the additional expenditure involved. These festive activities bring out the creative talents in women and children, and so naturally these are sources and occasions for joy. The joy is all the greater for women, because the activity is mostly for the children’s sake and naturally this affords satisfaction to the- mothers in the work. Children enjoy the festive food no doubt, but they also enjoy the creative activities equally well. It is this enjoyment that is reflected in the women folk, and for them these occasions are thus a source of double enjoyment.

Festivals are always a great source of joy for the children of the house. They give them enough activity, and give them more to eat also. All festoons with mango leaves are made by them. Their competition with other children in this work gives them ample scope for their creative activity to express itself. Long hours they spend over this and they also learn by copying the hand work of children more clever than themselves. The expectation of good and sufficient things to eat whets their eagerness to do a good decoration. Besides decoration, they do other work such as casting the image of Ganesa for Ganesa Chaturthi, arranging books and dolls for Sarasvati puja, cleaning the house of cobwebs etc. for every festival, and so on. Naturally they get plenty of good things to eat – sweets on New Year’s Day, Chitra Annam or Adipperukku, varieties of Kolukkattai, Jambu fruit, wood apple etc. on Vinayaka Chaturthi day, a number of dishes every day on the ten days of Dasarah, a large number of sweets at Dipavali time, sugarcane and plantain fruits for Pongal and so on. The gaudy dresses and visits to the Neighbours houses on the occasions of the Dasarah and Dipavali add an extra zest to the little girls.

Decoration – Festoons

The stringing of festoons in the house on festive occasions is part of the decoration programme. The entrance to the house is hung with festoons and they are hung around the place of the puja. The modern fashion is to purchase coloured tissue piper, cut it into pretty figures and string them. But up to the end of the first quarter of this century, paper festoons had no part in the festivities. People did very artistic decorations. but without cost. The tender coconut leaf shoots and palmyrah leaf shoots were used to prepare festoons. There was no need for the investment of any money on these. They were all had in any villager’s garden. The people cut one or two leaves, took out each bit separately, cut it to the required length with a sharp knife and plaited them into the required forms in a very artistic manner. The tender shoots were all white in colour and alternating with the dark green mango leaves, they presented a pleasing colour contrast to the eye. The coconut festoons dried and withered in about two days, but the palmyrah shoots never withered. They remained fresh for any length of time. So, after one occasion they were taken out carefully and stored, to be used for the next occasion.

Besides, many water lilies were available from local pools and ponds for the decoration. The lilies were generally available in white, pink and scarlet, and occasionally blue nilotpala; taken with the long stem, they were also hung round as festoons and as wreaths. Thus, all decoration was made without spending any pisa. Besides, the plaiting gave scope to the expression of the artistic talents of the people, particularly the children. They give with one another in working elaborate designs like the parrot and other fowl, the chariot, the rattle etc. on the coconut and palm leaf festoons.

Kolam

Kolam is an artistic symmetric design worked on the floor, done with fine white rice flour by dribbling it between the thumb and the forefinger, or by squeezing evenly through a piece of cloth staked in a solution of rice ground with water. The designs are intricate and elaborately done by the dexterous fingers of the women folk. There are countless numbers of such design’s done by the older women. Dots are placed evenly and symmetrically to weave round the outline of the design, and lines are drawn round them to achieve the desired result. Not only floral designs but others such as a temple car, a flower pot etc. are also woven. Those who are not nimble with their fingers use a small perforated tin cylinder and by rolling the cylinder the desired pattern is laid on the floor by the flour in the cylinder dribbling out through the perforation. In the earthern floors of the past, the wet flour design stayed for a number of days, but with the cement and the mosaic floors, it comes off immediately and the decoration does not have any great impact.

White rice flour was the only article used for kolam on all auspicious days in Tamil Nādu in the past. But now many colours are employed, by wider contact with North India, where rangoli or colour decoration patterns on the floor have been popular from long past Coloured rice flour and other material are used to add to the effect of the flour kolam of the olden days. Red earth, charcoal powder, dried green leaf p owder, yellow turmeric powder etc. are some of the natural coloring materials used.

We shall not say here anything about the urban practice of drawing kolams in what is called makku – mavu, which is just the mortar taken from buildings pulled down and powdered. This contains a large quantity of time and when drawn on a cement floor constantly it leaves a white discolouration. This is quite against the principle of the rice flour kolam,.which besides having the first purpose of decoration and beautification, has a secondary purpose of feeding other creation like the ants, squirrel and the crow. This expresses a concern for other life. While lime kolams (makku mavu) cannot.

Flour kolams are drawn not only on the floor but on all seat planks etc. , where any deity is to be invoked. They are drawn also on the ceremonial plank seats where the bride and bride groom are to be seated. There is no festival, ritual or ceremony without

Lamps

In every festival we have a lamp or many lamps. The lighted lamp is a symbol of God who is all Light. All the hymns of the Nayanmar and the Alvar hail God as the great Light. Before the advent of electricity, the oil lamp was universal. Even now, although the petromax lamps and the electric lamps are used for illumination purposes, in the sanctum and in the heart of the place of worship in all Hindu worship and rituals, only the oil lamp is to be used. The Kuttu vilakku, the tall standing lamp, or lamp combined with its stands is a symbol of Tamil Nādu art dedicated to God. Whatever may be the festival, any domestic worship or ritual, everything commences with the lighting of the lamp. Often, the deity to be worshipped or invoked on the lamp itself. Otherwise, it is placed in pairs., one at either side of the pedestal where the divinity is invoked. The lamp is the Dipam and at the commencement, the Dipam is worshipped as Dipa Lakshmi.

Needless to say, the temple springs into life with the lighting of the first lamp in the sanctum. There are lamps standing on the ground and lamps hanging by a brass chain from the ceiling, called sara vilakku. Electric lamps are not premitted into the sanctum. The lamp burns in oil or ghee, with a cotton wick. The lamp is considered to have life; the flame flickers and waves in the wind. This movement endows it with the quality of life, so very much recognizable by the devotees outside the sanctum; This becomes at once extremely artistic which the electric lamp can never become; it has no doubt much greater brightness, but no life.

The lamp is conceived of as God, as is evidenced by the rituals during any puja. The Kumkum and sandal are applied to it and flowers; also, is offered a neivedya. At the end of all the rituals a neivedya offering is again made and then the lamp is put out. The rule is that one should not blow on it with his mouth but should snuff out the flame with flower or a leaf petal, and then move it from its place near the Centre in token of the departure of Dipa Lakshmi.

The lighted lamp is the first item not only in all auspicious rituals but also in all inauspicious rituals. Not only for wedding but also for funeral ceremonies, the lamp is the first thing to be installed.

Many of our festivals are festivals of light. Everyone will remember the Dipavali, the row of lights with its crackers, and the Karttikai when hundreds of lamps are lit in every home and placed in every nook and corner including the cattle pen and other unused sheds. Light is also a symbol of joy and the joy is reflected on all these occasions. Parents even today take it as a matter of great privilege and joy to supply their daughters with ghee and wicks for lighting lamps on the Pongal day in their homes. Daughters living in very distant places get these by post well in advance. The Karttikai Dipam not only in Tiru Annamalai but in every small temple and in every small home is an occasion for lighting the heart. God is the supreme light that leads us from the unreal to the Real., from the evanescent to the Eternal, and from darkness to Light. No wonder the little lamp, which dispels, in however small a measure the darkness around is considered as a symbol of God, the eternal Light.

The lighting of a lamp in the soul was the occasion for the Mudalalvar – Poyhaiyar, Bhutattar and Peyar – to have a vision of Lord Vishnu in a dark corridor at Tiruk-Kovalur. A similar lamp is lit by Nakkirar on a later day to have a vision of Siva at Kailas. In modern times, Ramalingar tried to introduce the worship of the Joti the lighted lamp as the universal symbol of the Eternal Light.

In ordinary parlance, Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity; will enter only a bright home, and so there is the custom of placing a lighted lamp in the evening at the entrance to a house in token of welcome to Lakshmi. The new bride entering the place of wedding, in agricultural families, carried with her a lighted lamp placed on a measureful of paddy, nirai- nazhi, in token of joy and plenty. During aratis waved before newlyweds to ward off the evil eye, a lighted camphor is placed on the saffron coloured water before waving.

The lamp in some form seems to be a symbol of God or be used as an invocation to God. The Christians use a candle which is nothing but a lamp of solidified oil. On their All-Soul’s Day, they light candles in churches and in graveyards to all souls and saints. The Japanese, the Parsis and even the Muslims have their own day of the festival of Lights.

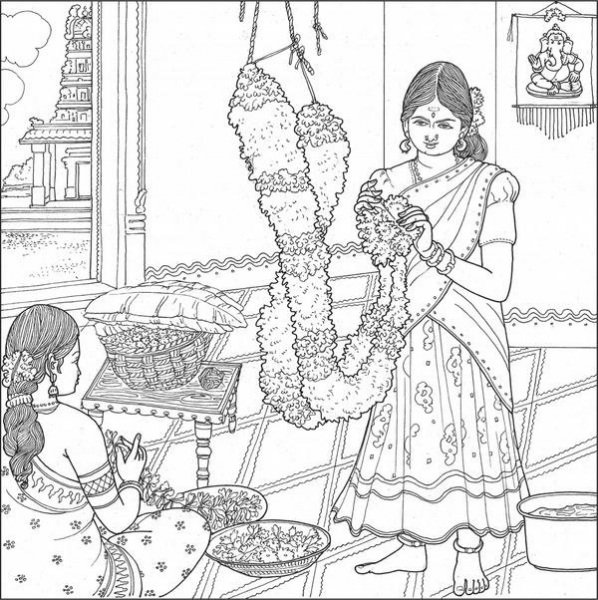

Flowers

India, particularly Tamil nad, is a country which not only enjoys but adores and worships flowers. Every small village here has a temple for Siva and the temple has a sthala vriksha or sacred temple tree. Any plant can be a temple tree. In the remote past, man came to see here a piece of stone in the shade of a plant and when he learnt to worship the stone as a symbol for God the tree which shaded the stone from the sun and rain and wind acquired sanctity and came to be worshipped. The number of such plants might well be several hundreds and the shrines where they are worshipped are several thousands. Huge trees like the banyan and the pipal are temple trees in several places, while the beautiful fragrant flowers like jasmine and chrysanthemum are also temple trees. Even the flimsy grass, the thorny carissa and the cactus, and the poisonous Calotropis’s are temple trees in some places.

All rituals for man here begin and end with flowers. There is no ritual without flowers. The common flowers are of course the jasmine varieties. Flower for any ritual domestion or temple means only the jasmine. Wearing of flower in the hair is part of the Indian culture, and fragrant flowers like the jasmine, the chrysanthemum, Champaka, Sampangi, nila Sampangi are the common flowers, to which list the rose has been added on the advent of the Muslims into India. Nonfragrant flowers were not generally worn by women but they are welcome to the deities. The very fragrant shoots of maruvam and davanam (artemisia) are favourites with women. They are interwoven for their green colour along with bright red, yellow and white flowers when making wreaths for the deities.

A reference to some of the flowers and their dedication to the gods will be interesting. The blades of aruhu (common hariali grass; are a favourite with Siva and Ganesa. The poisonous calatropsis is in great demand at the time of Ganesa Chaturthi for his worship. The vilva leaves (aegle marmelos ) and the Tulasi leaves (ocimum, basil) are special favourites of Siva and Vishnu respectively. The ordinary chrysanthemum (sevvandi) is the favourite of Siva at Tiruchirappalli and there is a puranam called Sevvandip puranam.

Tiru-atti (bauhinia), konrai (cassia) and tumbai (leucas) are again special to Siva, while the kadambu (the common cademba) and xetchi (ixora coccinea) are favourites of Muruha. Generally Siva is worshipped with white flowers

Red flowers are favourites of Sakti, and particularly sentbaratti, called jabakusam in Bengal is considered to be a special favourite of Sakti. The lotus is an important Slower for worship of all the deities. The white lotus is considered as the abode of Sarasvati, the goddess of Learning, while the red lotus is considered the abode of Lakshmi, the goddess of Prosperity or wealth. Talai ( pandanus) though fragrant, is taboo for Siva on account of a legend of Thiru Annamalai where talai gave false evidence to support Brahma. The margosa blooms and leaves perform various functions in the worship of Mariyamman and other similar deities of a lower order. Most of the flowers mentioned are available both in the cultivated and in the wild state. As insignificant flower named kanakambaram (barleria) is the raging fashion of urban areas, because it does not fade for many days. Where people do not bathe for days together, they are content with a flower which does not fade for days together. This is an orange colour and has many hybrid varieties.

Along with flowers we have to mention fruits. The two occur prominently in all our rituals and festivals.; Among the fruits the banana is the omnipresent fruit, considered in the Tamil Nadu, the poor man’s fruit. The Pongal season is the banana season and Pongal invariably conjures up before our minds thousands upon thousands of bunches of the banana and heaps upon heaps of the sugarcane. There could be no ritual of any kind in the home or in the temple without the ever-present banana. Every domestic celebration begins with the banana fruit. Palum Palamum, milk and the banana fruit, are the items first fed ceremoniously to the newly wedded bride and bridegroom who enter the father-in-law’s house for the first time. There are many varieties of the banana in Tamilnad, each area having its own favourite special variety. But one variety commonly known as poovan is the universal favourite; this is because it is available in all the areas and in all the seasons and at a relatively cheaper price. It is such a great favourite that banana in Tamilnad for any auspicious occasion means only the poovan variety.

The lime fruit is a symbol of auspiciousness and anyone visiting a ruler, a child or women, a guru or an official, if he cannot take any other present, is enjoined to take at least one lime fruit. The wood apple and the jarabu are favourites with Ganesa There is of course the mango festival. The jack is the sthala vriksha in Tirukutralam (Courtalam); Saint Tirugnana Sambandharhas sung a separate song on it as well as on the white jambu (Vennaval) which is the sthala vriksha at Tiru Araikka.

Of equal importance is the coconut offering. Along with the fruit, the coconut also is considered an essential food offering. Be it the temple or the home, the coconut is invariably present, with betels when the floral archana is over. When the food offering takes place, along with food (or in its place the banana fruit) the coconut is offered; it is broken in the middle, the water inside is poured out, and the two broken parts offered.

Food Arrangements for Festivals

There is an interesting association of food arrangements connected with many festivals. They have all been noted upon under their respective heads. Generally, on all festive days there is a sumptuous feast consisting of many vegetable dishes, vadai and payasam and banana fruits. Even in the case of vratas involving fasting, there is also a feast or festive food after the vrata is over. A further general note may be given here.

The year begins with the New Year Day, on which the use of the margosa blooms either in rasam or in pachadi has been considered important. The mango is of course the object of celebration in the mango festival which is confined to the Karaikkal region.

Next, we may think of the Adip-perukku festival when we have the kapparisi, rice soaked in water and mixed with jaggery and coconut chips distributed at the water front. For lunch on this day there is always a chitrannam, half a dozen varieties of specially prepared rice dishes., such as sarkkaraippongal, ven- Pongal, puliyardoia ellorai, tenkai sadam, elumicham sadam and dadyodanam, besides the modern vegetable pulav. Adip-puram has sprouted pulses.

The kolukkattai and modakam on the occasion of Vinayaka Chaturthi are something very special, along with a sundal, which are not repeated on any other day. The jambu fruits and vila fruits (wood apple) which are in season at this time of the year are also special offerings on this day. Puttu is the important dish for Avani Mulam and hard confectionaries like seedai and tengulal for Krishna Jayanti. The dasarah festival admits of all varieties of confectionaries. Dipavali has its own attraction in food, being, an occasion when as many sweets and salted dishes as the resources and time of the family permit, are prepared. The estables of this occasion are a source of delight for the children for atleast a week after the Dipavali. Karttikaip-pon, puffed rice mixed with treacle is the important item in the next month on the (Jay of the annual Kartikai festival. The two festivals, Vaikuntha Ekadeshi for the Vaishnavas and the Ardra Darsanam for the Saivas are the important festivals in Marhali and each has a speciality in food. Cooking the sesbania leaves as a dish is important for the meal on the Dvadasi day which breaks the fast of the Ekadasi. Similarly, Tiruvadiraik-kali, broken rice cooked with pulses and jaggery and coconut peels is important for the Ardra.

The Pongal food prepared with newly harvested rice on the occasion of Makara sankranti along with the rich fare of sugarcane and banana fruits is the most important among all the festivals, equalled probably only by the Dipavali sweets; Lastly there is the karadai for the Savitri nonbu.

So, this is a brief survey of the food traditions and the food preparations for the festivals of the year.

The Ritual of the Puja

Most festivals are attended with a kind of puja in the home? The puja prescribes a course of discipline, which may be elaborate in some cases, but basically the following are the chief features of the ritual. The members of the house have an early morning bath on the day (bath for most purposes means also bathing the head, not bathing up to the neck only as seems to be the practice in urban localities today}, a general cleaning up of the house, particularly the front and the puja area or yard, then a decoration with festoons and kolam. Festoons do not mean paper festoons; the rural economy being always a self-contained one, it does not admit expense on celebrations for available items. Festoons are prepared with mango leaves and artistically plaited tender white coconut leaves, which cost no money, while paper festoons involve expense.

Ingredients for puja are the same for all the festivals lamps with oil or ghee, flowers, fruits (chiefly plaintain), camphor and sandal, with betels; a bell and a plain seat (asana). Sugarcane when in season is added as in the case of Pongal. There is generally a cooked food offering which varies with the occasion. The object of worship is generally invoked on a pinch of vandal or turmeric etc. In some cases, a pot of water with mango leaves at the mouth with a coconut on top and with a cotton yarn woven round the pot is also placed for worship. This is called a puma kumbha (a filled pot). The ceremonial lamp in Hindu households is the oil (or ghee) lamps not the kerosene, gas or electric lamp, nor candle. The lamp is lit and the puja commences.

There is first an achamana, ceremonial sipping of water, then pranayama control of the breath; then Sankalpa or a resolution that I am going to perform this puja. A flower is placed first on the dipa (lamp) conceived as Dipa Lakshmi; then another flower is placed on the pedestal, asana; on the bell; then in all cases a Vignesvara puja (puja to Ganesa), invoked on a pinch of ground turmeric, with flowers and akshata and aruhu, Archana (flowers) aruliu (grass), patra (leaf) or askshata (rice mixed with 6andal or turmeric) is placed on the head and feet of the invoked deity; waving of dhupa (incense) and dipa. Then neivedya showing the food offerings including fruits, coconut and betels with a spoonful of water; and argya in token of His having accepted it. Dipa and karpura (camphor) aradana; then a suitable prarthana or prayer and pradakshina or circumambulation. People prostrate before the invoked deify and the sacred ash or Tulsai tirttam is taken as prasadam. Ganesa, or whoever it is, is now just moved a little to the right in token of the completion of the puja and the departing of the Being from this limited state to his or her all pervasive state. Then the people of the house have their food. Until the puja is completed the people are usually without food for the day.

The Kalasa or Purna Kumbha

The deity worshipped is invoked in most cases on a pinch of sand or sandal, turmeric or even cow dung at the time of worship. Rarely as in the case of the Vinayaka Chaturthi is the deity invoked on a clay image of the real form, made for the occasion. In some cases, like Varalakshmi, the deity is invoked on a kalasa {kumbha) or pot of water. The kalasa or even ghata figures prominently in all pujas like Kumbhabhisekha for temple puja for shashti abda purtti and so on. Water is one of the five elements and is also one of the eight forms of Siva ( ashta murtta) and invocation of God on a pot of water seems to be a favourite mode of worship. For all yagasala puja we have the ghata (pot). The ghata is conceived of as the body of God. It is wound round on the outside with white cotton yarn which is said to symbolize the nerves of the body. It is filled with water., preferably river water, all rivers (running streams) being conceived of as the sacred Ganga. Small quantities of fragrant spices are dropped into the water. Coins, gold and gems (where people can afford these) are also dropped in to the pot. The pot is filled nearly to the brim with water and purified by the incantation of powerful mantras. A bunch of mango leaves is placed on its mouth, on which a coconut with husk removed, retaining its tuft alone is placed, with its tuft pointing up. It is decked with turmeric, sandal, Kumkum and darbha grass tied into a knot (kurcham), and flowers. Usually, paddy or rice is spread on a plaintain leaf and the pot is placed on its midst. Some akshata (rice mixed with sandal, and flowers) is spilled on the head of the coconut at the top of the pot.

All the usual pujas are done, offerings are made to the kalasa and after the puja, the water in the pot is sprinkled with the mango leaves over the worshippers and their families or on the places sought to be purified (as in the case of a graha pra- vesa or a punyahavachana ceremony). The mantras offered to the kalasa by the duly qualified priest are considered to effect the purification. When this kalasa is taken and presented as a token of welcome to a distinguished visitor or acharya, it is called a puma- kumbha reception.

In Saivism, Siva can be worshipped only on three forms-the Sivalinga , the various Murtis such as Nataraja, Chandrasekhara, Somaskanda etc., and the kalasa’, these three also known as the sthamba, bimba and the kumbha. No picture or yantra is generally permitted.

The Kumbha is known by various names as purana kalasa, purana ghata, mangala kalasa, ghata etc. This is an artistic symbolism which goes back to the Rig Veda. The purana kalasa is symbolic of the human body which overflows by the Grace of God with all kinds of bounty. It is also symbolic of the pot of nectar (amirta ghata) which contained the nectar, obtained according to the ancient legends, by the churning of the ocean to milk. It is significant that Siva enshihed at Tirukkadavur in the Kaven delta is known as Amirta ghastesvara and at Kumbhakonam, He is known as Kumbhesvara.

Light and Sound

Although all the Indian festivities, whatever they be, have a common spiritual core, yet the average man takes to them with a riotous enthusiasm. Higher levels of society take to it with song and music, flowers, sandal and sweets. But to the ordinary people a festival is full of sound and noise, a boisteous merry-making. Children drawing a tiny chariot to the river front for Adipperukku, the procession of the clay image of Ganesa for immersion in the river after the Ganesa Chaturthi festival is over, the Navaratri celebrations of gorgeonus colour and varieties of eatables, the drums on the Pongal occasion in the Madras area are all attendad with great noise. The occasion of the Mattuppongal and its attendant worship of the cow and its madu-mirattal call for the greatest amount of hilarity. Women folk have a great part in the festivities for Adi perukku; Navaratri is theirs exclusively; and they are now appropriating a greater share in the Dipavali celebrations. The crackers and fireworks on the occasion of the Dipavali provide both light and sound to people at all levels – young and old, rich and poor, educated and illiterate. The ingenuity of the cracker manufacturers at Sivakasi is bringing into the market newer and newer varieties which are both a source of delight to the children and of drain on their parents’ purses. But on the other hand, the Karttikai day throws the children on their own resources and brings into play their powers of creativity in making the Kartikaip-pori, causing the whole early night appear like a world of bright stars floating on the air.

The Karttikai-pori by its very nature yet continues to be a great village celebration and it is hardly likely its ingenuity and charm can ever migrate into the city. Fireworks, even apart from Dipavali seem to have come to stay. They provide both light and sound and enliven the midnight hours by their display of the rainbow colours .They play a large part today in all temple festivities and the temple procession at night and seem to steal all the show. Large amounts are spent thereon in every temple. There are some experts in every locality who specialize in fireworks, and they are given the responsibility of putting up a bright and noisy show. This temple show has also invaded private homes, when marriage processions also indulge in variegated and costly though attractive, firework displays Political parties also are vying with one another in fireworks display. Not only children but even grown-ups indulge in this and a, pear to take immense delight therefrom. This trend is to be deplored. Our opinion is that all this has been overdone and needs to be put an end to or at least curbed. There is no great harm in mild fireworks display in temple processions but otherwise this has to be stopped altogether.

Festivals in the Temple and in the Home

There is no clear marking line with, us to indicate temple festivals and domestic festivals. Since every festival has a spiritual core, such a distinction cannot easily be made and is not necessary. Dipavali, Pongal, Adipperukku and some others may appear to be domestic festivals but here’ also there fs some temple involvement. For example, on the Dipavali day, all the deities in the temple are clad in new vastras and this requires the attendance of the entire village for temple worship. On the Mattu-Pongal day, people go to the temple after the Madu-mirattal is over and the cows are carefully tethered in the pen for a darsan and a prasadam of veppilaikkatti a mixture of lemon leaves and chillies powdered together.

Although temple festivals appear to be only religious, they are not mere temple celebrations but do involve some social values. For example, the Ardra darsan is specifically a temple festival, although ere worships Nataraja in the home also. But yet it is also a social celebration in this seme that in every household the Tiruvadiraikkali forms the unique and indispensable factor.

So also, with regard to Vaikuntha ekadasi. People may wait in long queues for the opening of the sorga vasal, the Gates of Heaven, but it does not stop there. It. is taken into the home in the observance of the Paranai ( paranam) i.e., the break of the fast on the previous ekadasi day, now at the dvadasi time and in the requirement of partaking of the ahatti (sesbania) leaves in a side dish., as part of the ritual.

Similarly, there is the pori or puffed and sweetened rice on the Karttikai day; there is of course the grand celebration in the temple. Children have a gala celebration for the better part of the night with their lighted Karttikai pori revolving round their heads making the whole village a heaven of luminous stars on earth. All these go to highlight the element of joy manifested in the eating part prescribed or observed by long custom as part of the temple ceremony.

Festivals like Vinayaka Chaturthi and Sarasvati puja are of course both temple celebrations and home celebrations. The above instances are given to illustrate how a temple festival is inducted in to the home.