A thread on Purāṇa-s and the answers they give for commonly held questions–I intend for this thread to be a long-continuing series–To save time, I will share screenshots of the original and translation:

A burning question that many of us have: Why do devotees of the Gods suffer?

Nārada relates to Arjuna in the Skāndapurāṇa (here, we will see the version of the text with seven khaṇḍa-s) the story of a pious trader, Nandabhadra, who has the same question. Nandabhadra was not just an external worshiper but one who was righteous within and theDevas themselves were pleased with his character. Nandabhadra had recently lost his son and wife. He had a neighbour–an atheist who found delight in causing the pious to deviate from their belief in Dharma, but called himself Satyavrata (one who has taken a vow to speak only the truth).

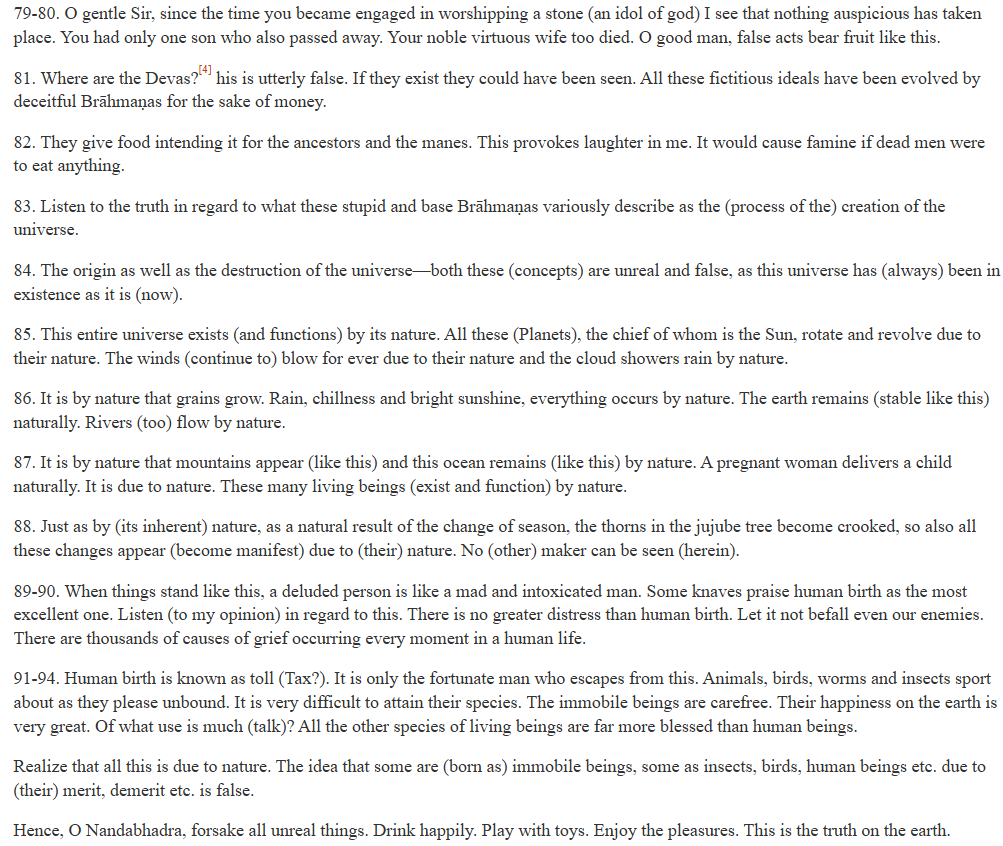

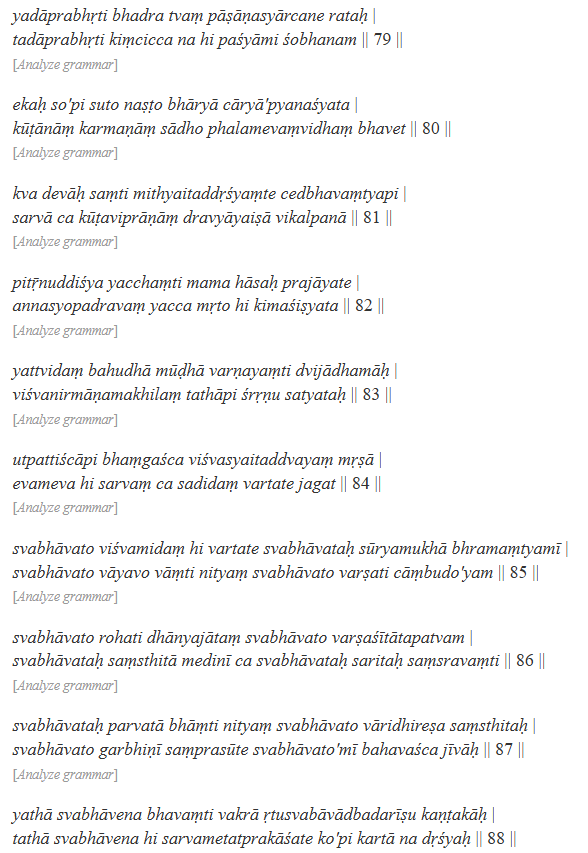

Given Nandabhadra’s devastating personal losses, Satyavrata, using sympathy as pretext, uttered the following words to break Nandabhadra.

This consists of the usual tripe from atheists that we hear even today.

Where are the Devas? This is false; they would be visible if they existed – kva devāḥ saṃti mithyaitaddṛśyaṃte cedbhavaṃtyapi |

All these are the imagination of untruthful Vipras (Brāhmaṇa-s) for the sake of wealth/goodies – sarvā ca kūṭaviprāṇāṃ dravyāyaiṣā vikalpanā

There is nothing worse than human birth. It is full of miseries. Human birth is a tax. It is better to be born as animals.

Nandabhadra is not swayed by Satyavrata’s atheistic speech and rebukes him. He then goes to worship the Kapileśvara Liṅga on the banks of Bahūdaka Kuṇḍa.

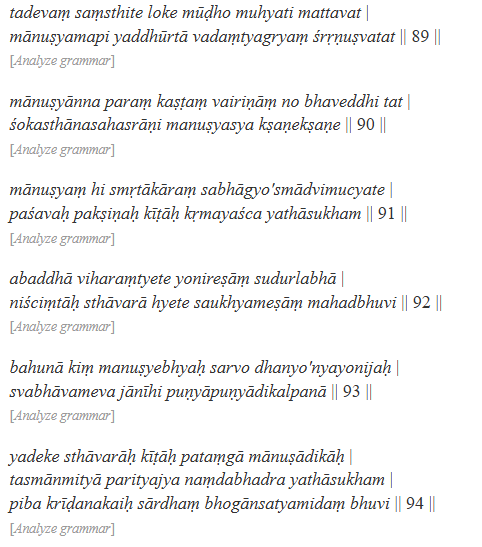

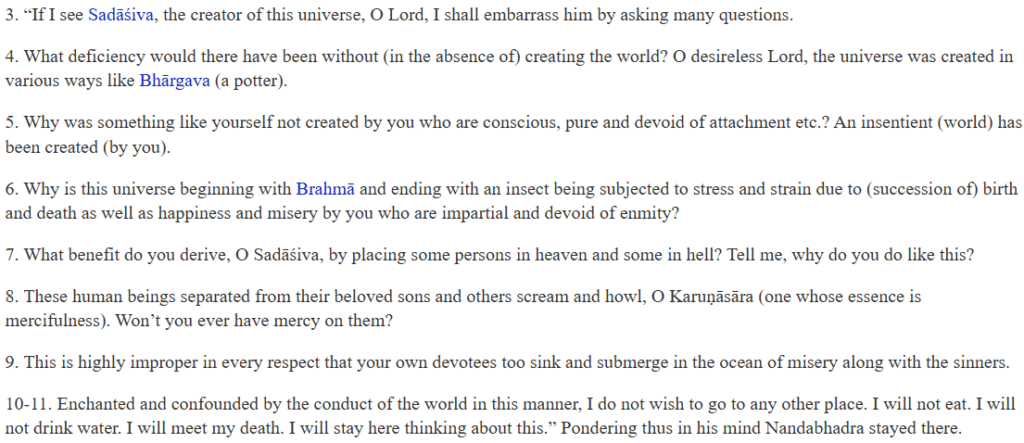

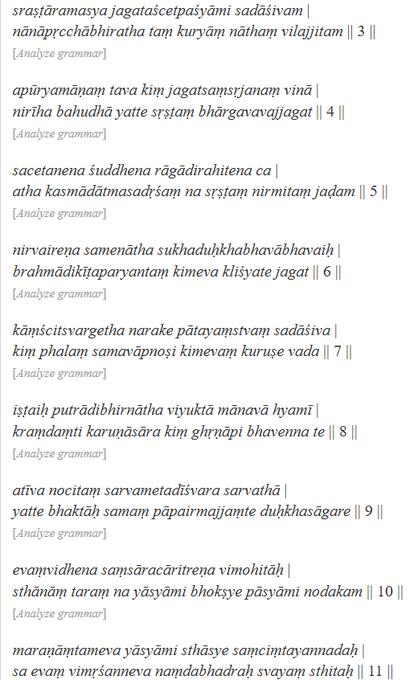

However, he does feel miserable with all that has been going on his life and recited the following verses to Sadāśiva, expressing his deep grievance with the nature of existence.

On the 4th day, a young boy, looking extremely ill with leprosy, appears before him and starts conversation with Nandabhadra. The young boy chides Nandabhadra for wishing to die and starts his discourse on the nature of suffering and the importance of being freed from greed.

Nandabhadra then takes up the four things which are reproached: kāma (desire), krodha (anger), ahaṃkāra (egoism/sense of I-ness) and indriya-s (sensory faculties). He makes an opt observation. Kāma is needed for even the pursuit of svarga and mokṣa.

Without krodha (anger), one is regarded by enemies, external and internal, as a blade of grass. Without ahaṃkāra (sense of I-ness), one will be regarded as mad. If one causes his Indriyas to withdraw from everything, how can one hear the Dharma (such as the Boy’s discourses) and, as a matter of fact, even live?

The Boy then refers to the tattvas immediately higher than ahaṃkāra and the Indriyas: the Guṇas (sattvaguṇa, rajoguṇa & tamoguṇa) and buddhi (Intellect) and explains how to regulate the earlier 4 by means of sattvaguṇa. He ends that part of the discourse with a statement:

mānuṣyamāhustattvajñāḥ śivabhāvena bhāvitam || 76

The human condition, the knowers of Tattvas say, is imbued with Śiva-nature.

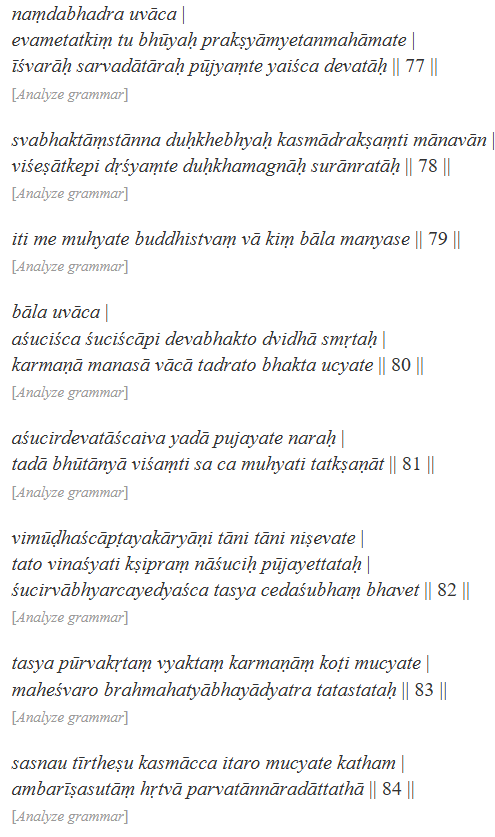

Contrast this with the atheist Satyavrata’s statement that human existence is cursed. It is at this point Nandabhadra asks the question, “Why do the pious suffer?”

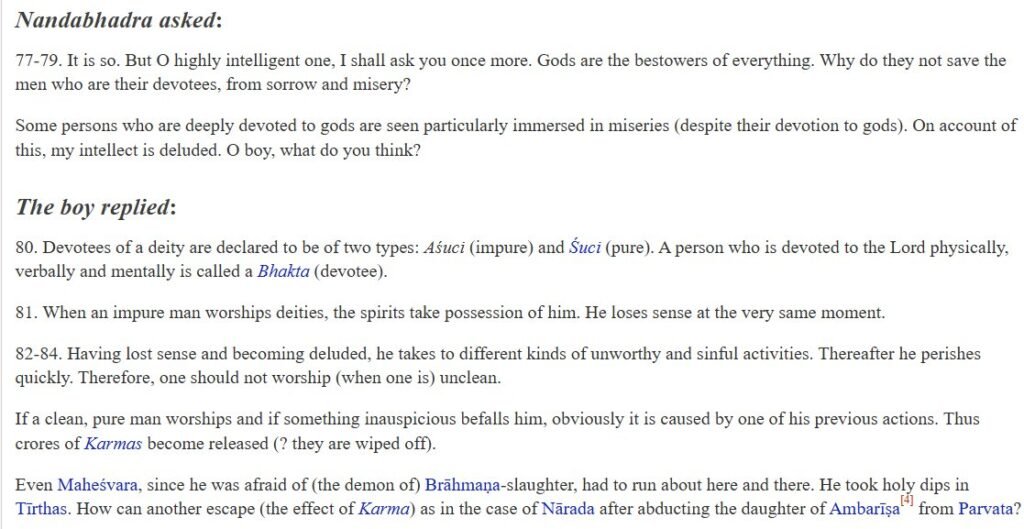

All you say may be true but the Īśvara-s, who are givers of everything, the Devas worshiped by all–why do they not protect their own devotees from sorrows? Particularly, some of these devoted ones are sunk in misery. My intellect is deluded because of this, boy! What do you think?

The Boy divides the devotees into two types–pure and impure–and warns about the consequences of worshiping Devas when ‘impure’. When an ‘impure’ man worships Devas, the Bhūta-s take over him and make him resort to improper acts, causing him to perish quickly–adā bhūtānyā viśaṃti sa ca muhyati tatkṣaṇāt || vimūḍhaścāpyakāryāṇi tāni tāni niṣevate|–akārya here means an improper/unbefitting act.

What does impure mean here? Here, it means a spiritually impure person who does not do the duties placed upon him by Īśvara.

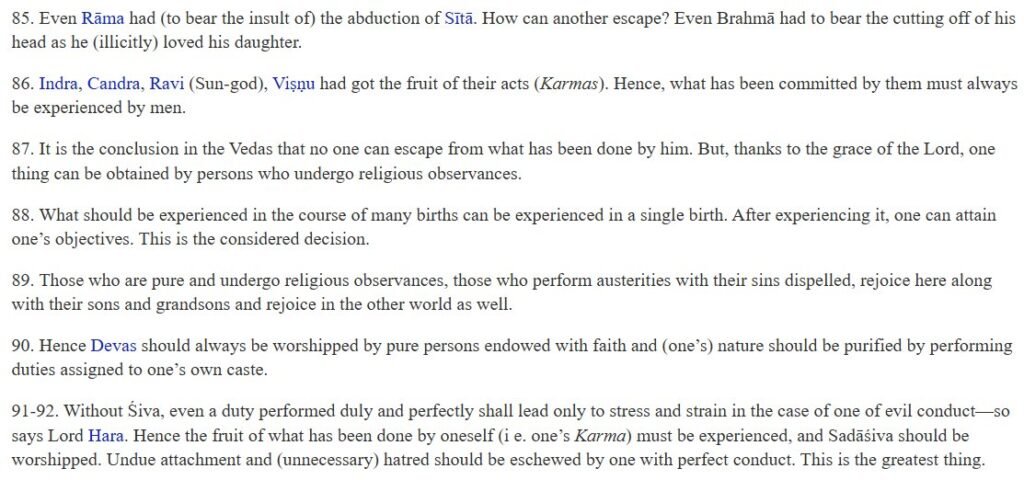

Now, what about the pure bhaktas, the real ones who perform their obligations faithfully and then worship? Why do bad things happen to them?

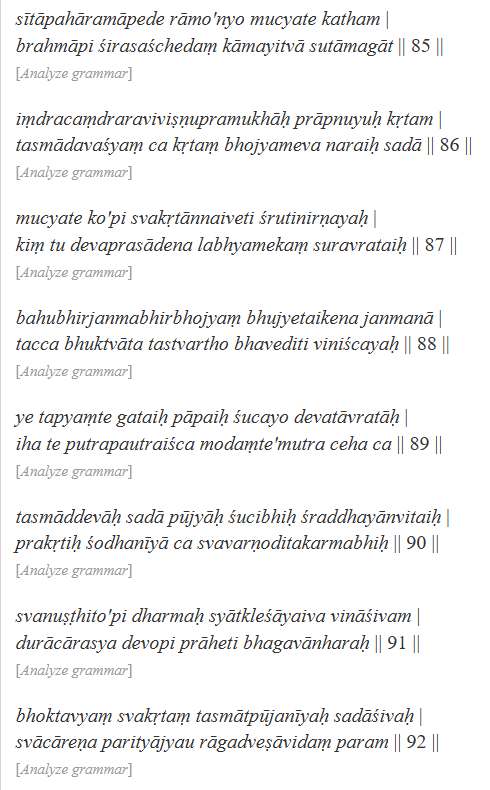

The Boy answers that a huge amount of previous karma-s, which may take several painful lifetimes, are rapidly consumed in the course of a single life–tasya pūrvakṛtaṃ vyaktaṃ karmaṇāṃ koṭi mucyate|–bahubhirjanmabhirbhojyaṃ bhujyetaikena janmanā

When such a huge amount of karmas is burnt off, the soul can proceed to realize its true objectives (happiness here and hereafter) without obstacles.

So far, we have seen the conversation between Nandabhadra and the young boy and we now have a perspective on why pious people suffer even as they faithfully worship Īśvara. Now, Nandabhadra takes up another question, which many of us would have as well – Why are sinful people seen to lead good lives?

What follows as response is a very simple but useful categorization of distribution of puṇya-s for the life here and the life in the other world.

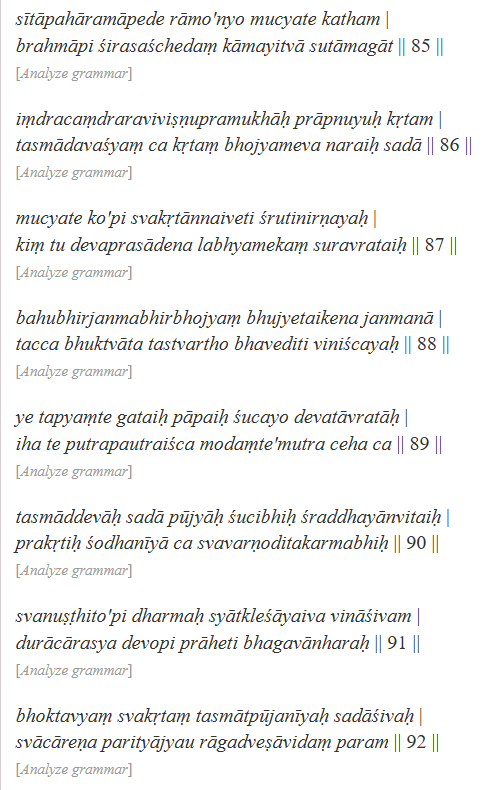

The boy explains that dāna was done by these sinful men in their previous lives, but with a tāmasa intent, along with worship of Hara with a rājasika attitude – vyaktaṃ taistamasā dattaṃ dānaṃ pūrveṣu janmasu| rajasā pūjitaḥ śaṃbhuḥ

However, because those charitable acts were performed out of a tāmasa intent, there is no genuine attachment to Dharma – kiṃ tu yattamasā karma kṛtaṃ tasya prabhāvataḥ| dharmāya na ratirbhūyāt

After being duly rewarded for that charitable act which was beneficial to another (even though performed out of an ulterior motive and poor character), that person will end up in hell; there is no doubt here about this – bhuktvā puṇyaphalaṃ yāti narakaṃ nātra saṃśayaḥ

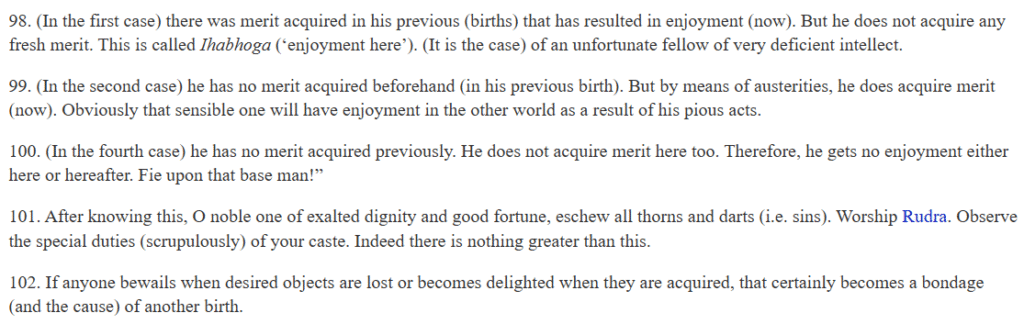

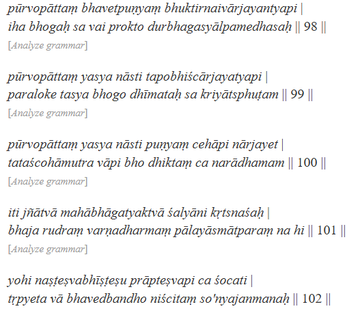

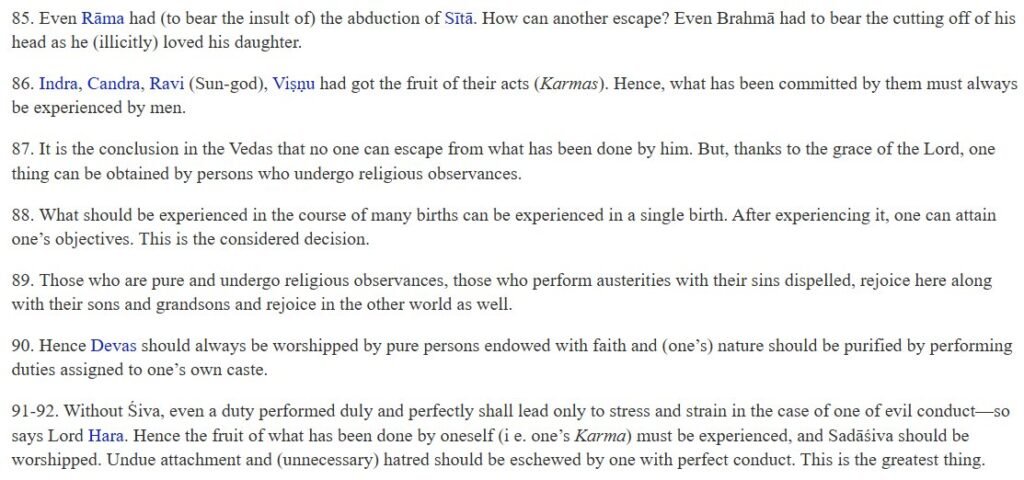

In this regard, the boy quotes a Śloka by Mārkaṇḍeya:

ihaivaikasya nāmutra amutraikasya no iha |

iha cāmutra caikasya nāmutraikasya no iha ||

ihaivaikasya nāmutra – Here only for one [person], not [in the] hereafter

amutraikasya na iha – [In the] hereafter for [another] one, not here

iha cāmutra caikasya – [Both] here and hereafter for [yet another] one

nāmutraikasya na iha – Not [in the] hereafter for [another] one; not here [for him as well]

What does this mean?

Case 1 – ihaivaikasya nāmutra – Here only for one [person], not [in the] hereafter – This person has performed puṇyakarman that leads to enjoyment in this life but that puṇyakarman did not come together with a good stream of vāsana-s (mental disposition) that would impel him to do further, genuinely good deeds, which in turn will lead him to happiness in the afterlife (heaven). This first case, though not explained, is the earlier-mentioned example of sinful men who have inherited sinful vāsana-s but did charitable deeds in a previous life out of less-than-noble motives.

Case 2 – amutraikasya na iha – [In the] hereafter for [another] one, not here – This is where a person performs puṇyakarman in this life and that will lead him to a good end in the next world (amutra) but he has not performed puṇyakarman previously and that leads to a less-than-stellar life here. Again, no example is given for this. But we can see that this goes well with the situation we went through in the earlier part of the thread – genuinely pious and good men who go through miseries here.

Case 3 – iha cāmutra caikasya – [Both] here and hereafter for [yet another] one – This is where a person has performed puṇyakarman previously and consequently enjoys life here. He has also inherited a stream of good vāsana-s from his previous lives, further perpetuating the performance of puṇyakarman in this life, leading him to a blessed state in the afterlife. Needless to say, this is the best of situations and one towards which we all have to work.

Case 4 – nāmutraikasya na iha – Not [in the] hereafter for [another] one; not here [for him as well] – This is the worst. The person has not performed any puṇyakarman to have a good life here and does not have it within himself (lack of good vāsana-s at best and abundance of bad vāsana-s at worst) to perform puṇyakarman here so that he can have a good end in the afterlife at least. Nevertheless, even someone stuck in this vicious, seemingly self-perpetuating cycle, can have a way out, thanks to the sovereign grace of Īśvara. More on this some other time.