Absence of Festivals in Vaikasi and Ani

It is interesting to note that, generally speaking, all the major festivals of the Tamilnadu are spread out through the twelve months of the year. Beginning with the month of Chitrai the first month, to Panguni the twelfth month, we find some major festival in every month. The Poompavaippadikam of Sambandhar also mentions them in order.

However, when we examine the full and long list of monthly festivals observed in Tamilnadu, we may note that there are no great festivals in the two months Vaikasi and Ani. (There are of course minor festivals in both the months, like Vaikasi Visakam which is special to Muruha, Ani Uttiram which is special to Nataraja known as Ani Tirumanjanam, and the Mango festival of Karaikkal on the Pournami day of Ani which is special only to the area round Karaikkal. All these stop with being mere temple celebrations.) Even in the first month of Chitrai, there is only the New Year’s Day festival on the first day of the month and year, as a great national festival.

There is a social explanation for this fact. The Tamil country is a tropical country where the summer is severe during the three months of Chitrai, Vaikasi and Ani. In the delta areas, all rivers are dry and even the village tanks will be fast drying up, because of the sun’s heat. There is generally no rainfall. Festivals which are a cultural heritage of the people are most enjoyable only when there are large sheets of water around in tanks and in running streams. So, since there is not that much of water in these months, festivals also have been few at this period, from the ancient past.

There is another and a more important reason. The festivals in general are celebrated everywhere, not only in Tamilnadu but the world over, only by the rural folk. They constituted in the past, and even today they constitute, a major part of the population. These people are mostly engaged in agriculture and only during these few months are they free from farm work. The rural community is now free to attend Festivals of Tamilnadu to other work. Weddings in rural communities are a great social event, and the people had set apart these months for marriage celebrations. It is also noteworthy that weddings are generally not celebrated in the agricultural communities in the months Adi to Panguni (August to March), as these months are a continuous season of agricultural operations. The few that do take place in Avani and Thai are exceptions.

Marriages in rural communities are always large social gatherings where people, relatives and friends, move out from distant places and congregate in the place of the wedding not for a single day, but for a few days, ‘four days’ as marriage invitations in the past used to specify. The wedding actually relates only to one house in the community, but all the families in the village suspend their other activities and engage themselves in the work connected with the wedding, for the four days. Hence, they cannot afford to have any distraction in the form of any other public festivity during the period.

Here people not only meet to participate in the wedding festivities and bless the bride and bridegroom, but also meet to discuss many affairs relating to the whole year and then depart. Talks and negotiations for fresh alliances are also carried on now, to culminate in the wedding ceremonies at the next wedding season. All this requires considerable leisure, and the getting together of the people of the same class for some length of time.

Marriage functions are the occasions for these talks and necessary plans, and only these two months in the year afford the leisure. Hence the entire community stops all kinds of other festivals, which were in a sense socio-religious gatherings and not pure social gatherings. Thus, this period of about two months was reserved in the distant past solely for this purpose. These may easily be seen to be the reasons for the absence of major festivals in the two-month Vaikasi and Ani.

Festivals round the Calendar

There are a little more than a dozen important festivals which take us round the calendar, and we shall just tabulate them here. They will be discussed later in the usual course in detail along with the others which are of a minor importance. We shall enumerate them on the basis of the Tamil calendar. These have been celebrated for ages past, for centuries before Indian independence was won, and long before the Spirit of nationhood in the modern sense took shape.

CHITRAI 1. The First of the month – Tamil New Year’s Day.

2. The Chitra Pournami.

VAIKASI Visakam, special to Muruha.

ANI The mango festival in honour of Saint Karaikkal Ammai. The Tirumanjanam of Nataraja at Chidambaram and the abhisheka to the Nataraja temples in every place. These have only a secondary importance.

ADI 3. Adi 18th, Padinettam Perukku.

AVANI 4. Vinayaka Chaturthi. The Avani avittam or Upakarma and Gayatri japam for the brahmin community.

PURATTASl 5. Sarasvati puja and Ayudha puja with the attendant Vijaya Dasami for the entire TamilNadu. Krishna Jayanti celebrated in urban area and mostly only by the brahmin community.

AIPPASI 6. Dipavali.

7. Skanda Sashti.

KARTTIKAI 8. Karttikai Dipam:

MARHALI 9. Arudra Darsanam

10. Vaikuntha Ekadasi. The last day of the month as Bhogi pandihai

THAI 11. 1st as Pongal day.

2nd Mattup-pongal day.

3rd Karinal day.

MASI 12. Masi Magham.

13. Maha Sivaratri.

PANGUNl 14. Panguni Uttiram.

Sri Rama navami.

Here we have a list of fourteen festivals which may be called the National Festivals of Tamilnadu, although some of them are also National Festivals of an All-India character, such as Vinayaka chaturthi, Sarasvati puja, Dipavali and Maha Sivaratri. The above list includes a few festivals of lesser importance, but they have not been numbered.

When we examine the days of the festivals, we find there are some festivals which do not depend on any thithi (phase of the moon) or nakshatra (star) but are celebrated on fixed days of the monthly calendar. The following are some of them.

New Year’s Day— the first day of Chitrai, corresponding to the 14th of April.

Adip-perukku — The 18th of Adi, corresponding to about the 2nd of August.

Aippasi Kadai-mulukku — The last day of the month; corresponding to about the 15th of November and its sequel Mudamulukku on the next day the first day of Karttikai.

Pongal festival — Four days:

Bhogi — the last day of Marhali, January 13th.

Pongal — the first day of Thai, January Uth.

Mattuppongal— January 1 5th and

Karinal — January 16th.

Karadai Nonbu — The last day of the month of Masi – the conjunction of Masi and Panguni, about the 15th March,

Similarly, among the new national festivals which are evolved out of the political awakening of the peoples of India, the following are the most important and they occur on the specified dates without any kind of change.

The Independence Day — 15th of August.

The Republic Day — 26th of January,

The Gandhi Jayanti Day — 2nd of October.

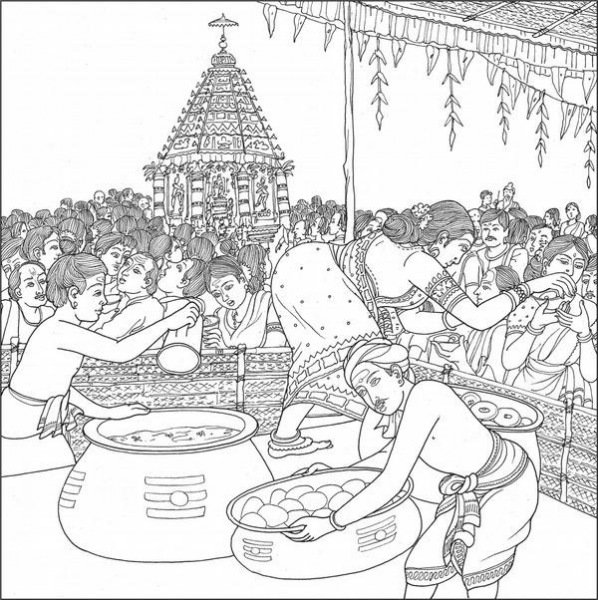

Festivals and Pilgrimages

Some of the most important temple festivals are regulated in a manner which will help the pilgrims to make their tours conveniently and at leisure; In the past there was no good road, and transport was either by walk or by bullock cart along muddy roads. Devotees had been by religion and custom enjoined to visit the important festivals at the major temples at least once in their lifetime. It appears as though all the festivals had been regulated in the past with a view to helping the itinerant devotees.

Devotees had been required to visit temples and worship the particular sthala or shrine, the form of Siva installed there, and also the tirtta, a sacred tank or river of the place. St. Tayumanavar of a later day would declare that when the spiritual aspirant goes on a tour of places, shrines and the sacred waters a competent guru will appear before him in a proper place for imparting spiritual knowledge to guide him forward in his god ward march.

There are not many major festivals in the first six (Tamil) months Chitrai to Purattasi. In the distant past, Avani and Purattasi were rainy months and so travel and pilgrimage were avoided. The itinerary began virtually in Aippasi. People were free to witness the annabhisheka in the temple nearest to them. Two other festivals important to them in the month, are the Shasti festival at Sikkil, near Nagapattinam southeast corner of the Tanjavur district, and the other the Kadaimuzhukku at Mayuram in the opposite northeastern corner of the district at quite a long distance.

The next month is Karttikai, and the most important festival is the annual Karttikai at distant Tiru Annamalai. Probably all persons might not have been able to afford the time and energy required for the purpose. Hence shrines nearer had been given equal importance such as Swamimalai Vaidhisvarankoil, Palani etc. Besides, every Sunday in the month of Karttikai is a festival at the shrines close to the Kaveri and we have such grand Sunday celebrations at Kuttalam, Tiru Nageswaram, Tiru Vanchiyam etc.

Marhali has two of the greatest festivals in all Tamil Nadu Ardra darsanam at Chidambaram for the Saivas and Vaikuntha Ekadesi for the Vaishnavas. The Gaja samhara festival at Valuvur near Mayuram (slaying of the elephant by Siva) is an equally popular festival on the early morning of the Ardra darsana day. Thai has the ancient Pusam festival at Tiruvidaimarudur. Masi has the Magham festival, celebrated on all waterfront shrines, with the famous Maha magham in Kumbakonam occurring once in twelve years. The last is a great event for which most people would have been planning years ahead.

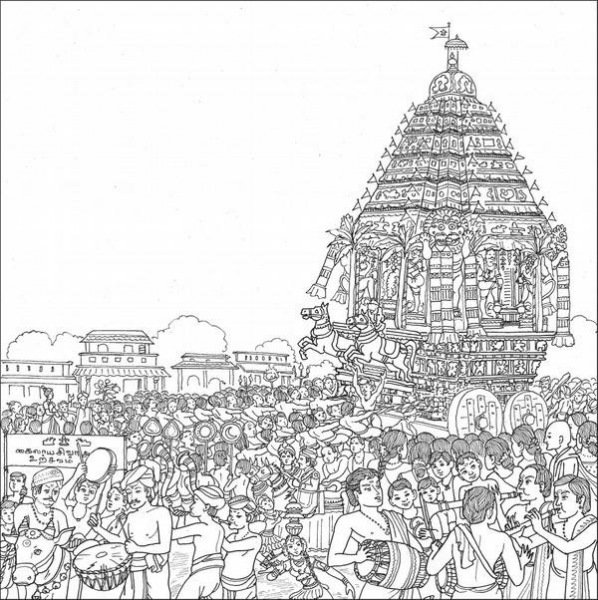

The last month of the calendar is Panguni which witnesses the annual temple festival of eleven days in every village and town called the Brahmotsava.

The modern day attaches special importance to the Arupattu muvar festival at Mylapore in the city of Madras, the festival for the Sixty-three Saiva Saints. The New year now begins with the month of Chitrai introducing the important festival called Tirumulaippal at Sirkali, the festival of the feeding of milk by Sakti to the child Jnanasambandhar. A festival of some importance is the Kala samhara at Tirukkadavur, the kicking away of Yama the god of Death, for the sake of the boy worshipper Markkandeyar.

This is the itinerary or tour programme of pilgrims who make it a point to worship at important shrines during the most important festivals there. It can be seen that the festivals and the places had been so distributed in space and time that pious persons have the requisite time to travel from one place to another after worshipping in each of the places. There were free feeding centres in all these places. Agrarian communities considered it an honour to feed pilgrims during festivals. Rice was in plenty, and money was of no account. So, people had no second thoughts about undertaking a pilgrimage.

The months Vaikasi to Purattasi did not have any such major temple festivals to attract large crowds. There are some like the mango festival in honour of Karaikkal Ammaiyar at Karaikkal and the Adi-tapas of Gomati ambikai at Sankarankoil, but they do not have the great national importance of the foregoing. Festivals at Madurai, Sri Rangam and Tiruppati are many; and in these places we have several festivals every month and so no particular festival and month need be specified for a pilgrimage to these places, Tamil people yet think of Tiruppati as their own place of pilgrimage and so it has been mentioned here. The place had been a Tamil city even as late as the Second World War and it is an accident of politics that it has gone over to the Andhra Pradesh.

Festivals round Pournami

The full moon day (Pournima) is a day of great joy and merry making in Tamilnad. This country lies north of the Equator and south of the Tropic of Cancer and so most of the year it is hot during the day. Hence the cool moon in the evening is always welcome and the full moon more so. The full moon days are always days of festive gathering.

We shall now examine the full moon days of the successive months. The first is Chitra Pournami, in the first month, celebrated today all over Tamilnad as a day dedicated to Chitra gupta the accountant of Yama Dharmaraja, the god of Death. This festival is generally restricted to the house itself and it is not any elaborate social occasion.

The pournami in Vaikasi, the second month, generally occurs in conjunction with the star Visaka. The Vaikasi Visaka is a special festive day for Lord Muruha in all the south Indian temples; Visaka is the star of the avatar of Muruha. The Vaisaka suddha purnima is also celebrated as the day of attainment of Nirvana by the Buddha. This is according to the lunar reckoning, and often it occurs in the Tamil month of Chitrai.

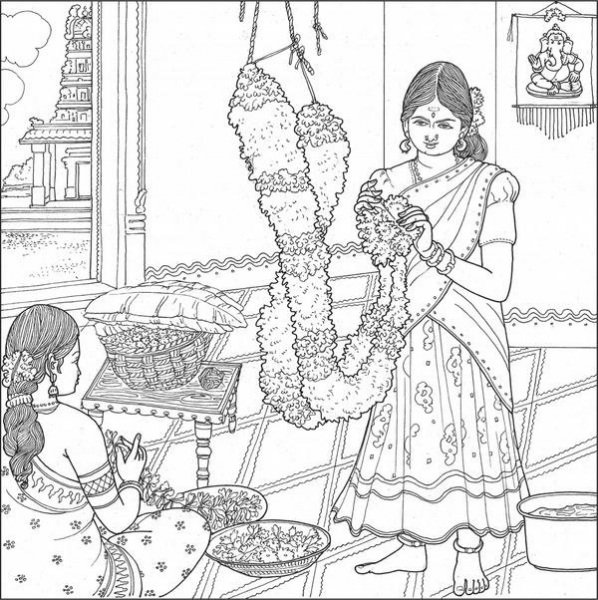

The pournami day in the third month of Ani is the day of the mango festival at Karaikkal. It is a rare and unique festival, although local, in this that it is a festival for a Saiva saint and a woman saint, Karaikkal ammai, and it is also a festival for a fruit.

The pournami day in Adi is the Guru purnima, where Vyasa puja is performed in honour of Vyasa, the legendary compiler of the Vedas, the writer of the Mahabharata which contains the Bhagavad Gita, and the traditional narrator of the Eighteen Mahapuranas.

The Avani full moon day generally coincides with the avitta nakshatra, which is the day of upakarma for the twiceborn, with its attendant Gayatri japa on the following day.

The pournami in the month of Purattasi is a day dedicated to the celebration of the plant world, called Niraipani Vizha when fruits and vegetables are hung around in display in the temples. (Pani is service, and niraipani is the culmination of the servicer) This is a kind of thanksgiving to God who was merciful enough to give a plentiful harvest to the people. Similar display of agricultural produce is also being done in churches in the western countries.

Ona vila was celebrated on the Aippasi full moon day in the past as referred to by St Jnanasambandhar, but it is not in vogue now. However, this day is important as the day of annabhisheka for Nataraja in Chidambaram, that is, the image of Nataraja is bathed in cooked rice symbolically and the large quantities of rice prepared and offered to Nataraja are distributed to the people. The same abhisheka and distribution are made in many other large temples like Tiruvidaimarudur, Tiruppanandal, Tirukkadavur etc.

The Karttikai full moon day occurs in conjunction with the Karttikai star, where the famous Dipam festival is conducted in Tiru Annamalai and all the other Saiva temples. This Karttikai is also the day of lights, when hundreds of lamps are lit in every household in memory of the Tiru Annamalai legend.

In the next month of Marhali the ardra constellation occurs in conjunction with pournami, and on the morning of this day is celebrated the Dance festival of Lord Nataraja, the greatest festival for Saivas in any part of world.

Pusam in the next month of Thai occurs on the Pournami day and it is a day of festival in all Siva temples, particularly temples on the riverbanks. It is a day of great celebration in Tiruvidaimarudur. It is also a day of significance as the day of the passing away of St. Ramalingam at Vadalur.

The pournami day of the next month Masi is associated with the star Magham. This is an important festival connected with the river and sea baths. The Holi festival of North India and (he Kama dahanam or the burning of Kama to ashes by Lord Paramesvara also occurs on this day. Kama dahanam or Kaman pandihai is a popular festival among all the rural labouring class of people today.

Lastly there is Panguni Uttiram on the Pournami day which is the day of the annual temple festival of ten days in all the important temples, called Brahmotsava.

This completes the cycle of the twelve full moon days of the year and the important festivals celebrated in association with those days and with a star, every month.

Festivals and the Phases of the Moon

As stated already, there are festivals round the calendar, celebrated every month. Every phase of the moon has important celebrations in different months.

The third phase, Tritiya: there is the akshaya tritiyai in Vaikasi, a day on which gifts are made and special temple celebrations are also undertaken. The fourth, Chaturthi, we have the very important festival, Ganesa chaturthi, in the month of Purattasi. The fifth, Panchami – the Nagapanchami and Garuda panchami in Avani and the Vasantha panchami in Masi. The sixth Sashti – Skanda Shasti in Aippasi, a Muruha celebration throughout Tamilnad. The seventh, Saptami – Ratha saptami in Thai, sacred to the Sun. The eighth Ashtami- This was an important festival in the temples in the past but somehow this has disappeared altogether. It is still preserved in the Gokulashtami festival, Sri Jayanti, sacred to Krishna. The ninth, Navami Sri Rama Navami in Panguni. The tenth Dasami, -Vijaya dasami sacred to Sakti and Sarasvati in Purattasi, The eleventh, Ekadasi, – Vaikuntha ekadasi in Marhali, the most important Vaishnava festival; Kaisika ekadasi in the bright fortnight of Karttikai which celebrates the story of Nambaduvan the harijan singer of Tiruk-Kurumgudi. The twelfth, Dvadasi – the day following the two ekadasis mentioned earlier. The dvadasi following Vaikuntha ekapasi on the day on which the previous day’s fast and vigil have been ended, is important. The fourteenth, Chaturdasi in Masi is held sacred to Siva and Sakti as Sivaratri. The Naraka chaturdasi, fourteenth day in the dark fortnight of Aippasi, is the most popular festival known as Dipavali.

The New Moon Day and the Full Moon Day have their own importance. A large number of people observe these days as days of vrata, days of special dedication to the departed ancestors. Particularly on the Amavasya (new moon) day, householders perform the tarppana or offering of oblation lo the departed souls of the family. The amavasya days in the months of Adi and Thai are considered especially important in this regard.

Festivals and Nakshatras

The Tamil calendar marks a cycle of 27 stellar positions commencing from Asvati and ending with Revati, A particular star is said to be on the ascendant each day. In this manner of speaking, we may say that the festivals are regulated for most of the stars. Some of them will be mentioned here.

Karttikai – the annual Karttikai dipam celebrated in all temples and homes; the chief temple being Tiru Annamalai. (Of course, the monthly Karttikai day also when many people fast as a religious observance for Muruha)

Rohini is the birth star of Sri Krishna. Tiru Adirai the Ardra darsanam, Nataraja’s dance at Chidambaram.

Punarpusam – the birth star of Sri Rama.

Pusam – the Thaip-pusam festival at Tiruvidaimarudur, Vadalur etc.

Magham – the Masi magham festival throughout Tamilnad.

Puram – Adip-puram festival for Sakti in all temples. Uttiram – Panguni Uttiram, Brahmot- savant festival in all temples;

Ani uttiram being the Anit-Tirumanjanam again abhishekam to Nataraja and His Dance at Chidambaram.

Hastam – in Panguni, the day of publication of Kamba Ramayana; nearly eleven centuries have now passed.

Chitrai – Chitra Pournami in the month of Chitrai which occurs in conjunction with the star Chitrai.

Visakam – Vaikasi Visakam festival.

Mulam – the Avani mulam festival in Madurai and other places in honour of Manikkavacakar.

TiruOnam in Purattasi, special for Vishnu.

Avittam – in Avani, Upakarma.

Classification of Festivals

In the account of festivals in this book the festivals are described following the order of the Tamil months in which they occur; no classification has been attempted here for the purposes of celebration. However, we may be able to classify them under four major heads, although there may be many Cases of overlapping. They will be the following heads:

Distribution of Festivals

1. Social festivals,

2. Religious festivals,

3. Literary festivals and

4. National festivals.

A few examples out of the traditional ancient festivals under each head may be mentioned:

Social – Dipavali, Pongal.

Religious – Vinayaka chaturthi, Avani Avittam.

Literary – Sarasvati puja.

National – New Year’s Day.

What may be called cultural festivals can easily be seen to come under any one of four heads. Some of the religious festivals are also temple festivals. There are besides some festivals which are merely domestic, i.e., confined to the one family where they are celebrated. Besides the festivals, there are many vratas which have an equal importance.

In the Sanskrit language, the puranas give accounts of festivals and the festivals may be said to have gained importance in society from the age of the puranas. Along with these, many vrata kosas have been compiled which deal with all important vratas which are always religious observances. They deal with the importance of a vrata, its occurrence, significance and manner of observance and the stories of those who benefited by observing the vrata concerned. Similarly, many classical books of a puranic character in the Tamil language deal with the vratas and important observances relating to the respective religions. As examples may be cited the Upadesa kandams by Koneriyappar and Jnanavraodayar, Brahmottara Kandam by Varatunga rama Pandiyar, Kurma puranam and Kasi Khandam by Ati Virarama Pandiyar, Machapuranam by Vadamalaiyappa Pillaiyan, and several others.

As has been explained in the case of each festival, many of them are religion-oriented and so associated with the local temple or some important temple of great renown in the whole country. But yet some of the more important festivals are not related to the temples. Many important ones are just social festivals. Examples ape the Tamil New Year’s Day, the Adip Perukku, the Pongal and so on. These are just social festivals, celebrated in the family and in the society unconnected with temple worship and without any puranic legend.

The Hindu religious festivals in Tamil Nad easily resolve themselves into Saiva and Vaishnava and they always run on parallel lines. Many festivals require a vigorous personal discipline, often accompanied by partial fasting. The most important days of complete fasting are two – the Maha Sivaratri for the Saiva and the Vaikuntha Ekadasi for the Vaishnava. They include fasting for the whole day and a vigil for the full night, with a breaking of the fast the next morning.

Similarly, two jayantis or birthdays of avatars, Rama and Krishna, are celebrated by the Vaishnavas on the Sri Rami Navami and the Sri Jayanti days. These have a parallel in the Saiva celebration in the Ganesa chaturthi and Skanda shashti which are not birthdays but are the days on which the forces of evil were overcome by Ganesa and Skanda respectively Ganesa and Muruha, considered to be the manifest forms of Siva Himself; are not held to be avatars and so a day for their avatar has nowhere been specified. Still Vaikasi Visaka is considered the day of the natal star of Muruha. All these are great occasions of fasting and rejoicing for entire families and communities.

These are religious festivals, no doubt. They are conducted both in the temples and in the homes Social and religious festivals have not grown afresh or multiplied. But with the passing of time and with the emergence of an Independent India, new national festivals and literary festivals, bearing both on the past and on the present, have risen up in large numbers. They will be dealt with under their respective heads.

Vratas

Since we referred to vratas in a previous paragraph, we shall say here a few words on the subject. Observance of some important sacred days by some form of personal disciple in is a feature common to all religions. We must remember vratas are different from festivals and that the two are not the same. (Vrata is a single concept which however calls for several connotations in English: It is a penance, a sacred how to observe certain austerities, including fasting, occasional vigils, continence etc.) Vratas have no collective celebration in society. They are purely individualistic. The person observing the particular vrata, fasts for the day or even from the previous evening and occasionally as at the time of Ekadasi and Sivaratri, even keeps awake for the whole night. It is not a social celebration for the whole family or for the entire community.

A few vratas are observed among all classes of the people but the smarta brahmins may be seen to observe scores of vratas. Sri Vaishnava brahmins hardly observe any vratas. The Jains may be said to observe the largest number of vratas in Tamilnad. There is a Tamil Jain work in manuscript called Nonbu-katthai (nonbu-Tamil for vrata); where 60 vratas are described in detail in the manipravala style. It is interesting to note that among the jain vratas are listed Ananta vrata, Dipavali, Maghamasa vrata, Sivaratri and Sri Panchami all of which can seen to be Hindu vratas even to this day.

People at all levels have a partial fast on certain days of the week and call it vrata of that vara; the most common are Somavara (Monday), Sukravara (Friday) and Sanivara (Saturday); on these days people either fast in the evening or take only milk and plantain fruits.

Many festivals are accompanied by vratas and partial fasting like Skanda shashti, Karttikai, Ekadasi and Sivaratri. Some vratas are also temple festivals. The fasting, even if it be for one day, or foregoing of one meal, has the salutary effect of an internal toning up of the human system.

There may appear to be a restriction on women observing any vrata. The tradition is that a woman shall not worship anyone except her own husband. Classical literature would make much of this element. In cases of pre-marital love, it is a sort of test to know whether a young girl has lost her heart to some lover. The girl is becoming thinner day by day and, to learn if it is really because she is lovesick, she is asked by her people to pray to the crescent moon. If love had not come into her life, she would straightway pray. But if she had set her heart on another lover, she would not consent to pray to the moon, because she cannot pray to anyone other than her husband or lover.

So that is the tradition. But if it were to be strictly enforced, no woman can pray, or go to a temple, or observe a penance or vrata. So, the same tradition would say that she can do all these – pray or observe a vrata- with the consent or permission of her husband. Thus, women may be seen to be free to observe vratas; in fact, it is mostly the women who observe the vratas.

Some vratas have been described in the text. Uma Mahesvara vrata and Somavara vrata are some of the more important vrata.