Festivals are fountains of joy for all. They exist in all countries, in all levels of society, in all races, and had been existing through all the ages. If man has been described as a social animal, festivals are the occasions for a close joyous coming together for the members of the social group, and they give full expression to the social instinct.

Festivals seem to be universal. They have been natural to man at all climes, in the past and in the present. Joy is inherent in the human being and only when there is an impediment in its fulfillment and experience, does sorrow arise. Sorrow is not inherent in man. The expression of joy is rejoicing and rejoicing means not one but many, means society. Sorrow becomes less and less oppressive when shared with others, while joy increases by sharing with others. This is the reason why sorrows like death, and rejoicing as at a wedding, are all social events the world over.

The expression of the greatest joy and the occasion therefor is called a festival. The best of any nation can be seen only in its feasts and festivals. These in turn imply a comradeship, fellow feeling and sharing; in short it is in a sense the expression of some of the best traits in man. The primitive man or the civilised man, each has loved festivals and rejoicing. Hunger has made man no doubt inventive but this inherent joy in group festivities and rejoicing have made man cultured and civilised.

The Tamil word for festival is Vizha (vizhavu); this arises from the root, vizhai , to desire and to love; the noun means the thing desired, the object celebrated. So when the narrow love expands, it expresses itself in the form of festivals and celebrations. The Sanskrit word is utsava (festival, jubilee) which is derived from a root meaning to rise upwards; so this is going upward, getting elevated. In the English language also the two words feast (joyful religious anniversary) and festival (celebration) are very much the same. All these have the general connotation of a celebration. Vizha is called also Kondattam, which word has the additional element of dance in it.

It is not possible to go into the question of what causes man to celebrate a thing and what gives him joy. The very getting together draws forth spontaneous joy. We may not probe into it further and try to see the reason behind a celebration. Whatever gives joy, man continues to do, and thus festivals have taken root – joyous occasions and occasions for festivity no doubt like child-birth, marriage and so on. Tamil literature would point out instances where even wars had been occasions for festivity.

Death is by its very nature the opposite of joy and so we may believe that it was only an occasion of mourning. But in fact, it is not so. Mourning is confined to a period of 15 days; then mourning stops and festivity commences. The reasons are not far to seek. It is that no one should be allowed to be steeped in mourning for long. One should get out of it and become normal, enjoying the pleasures of life. Hence in every case of death, there is a ceremony on a particular day (10, 15, or 16th) after which there is no mourning. The second reason is our faith in the indestructibility of the soul. The soul inhabiting this body has now given it up, to take up some other body. Why then need we grieve for long?

So the festivals go on. Men in the ancient agrarian society, always went out for work and so festivities became the chief concern of the women folk who stayed behind. Women in the past, till the liberation movement, had been of a self-sacrificing nature, always working and keeping the home warm and delightful both for their husbands and for their children. Kural would say that the duty of the house holder (grhasta, illarattan) was to take care of the five – the manes (dwelling in the southern regions), the deities, the guest, the kin and the family. This duty was rightly fulfilled by the women folk. That is also the secret of the continuity of the heritage of the festivals and their success.

Now every important occasion in the life of an individual from birth to death is a domestic festival or ritual. As a matter of fact, these rituals begin even before birth. During pregnancy, there is the Valaiyal kappu, known also as poo-chututal, {a kind of Raksha bandhanam). Then in due time, the birth, namakarana or naming of the child, perhaps along with the first placing on the crib, ear-boring and the celebration of the first anniversary of the child’s birth. The annap-prasana or the day of feeding of rice to the baby, then the upakarma among brahmins, placing the child in the school, and lastly the wedding. These are a total of sixteen and each is in some measure, large or small; a domestic festival.

The cycles of natural events are themselves great events. Sunrise and sunset call for special prayers, Sandhyavandana ; so also the new moon and full moon days call for special tarppana. We shall see later the part played by the full moon days etc. in the matter of festivals. So also the equinoxes or ayanas, and eclipses. All these call for special baths in a river or the sea. Eclipses; though recognised as mere natural phenomena by astrologers and calendar makers in the past, have yet been the source of many romantic legends. Many occasions symbolise the rejoicings in the family, such as the Pongal, which really celebrate agricultural operations. Adipperukku is also similar, denoting the commencement of agriculture while the other, pongal, celebrates its culmination.

In between we have the days of great heroes and of forms of deities celebrated such at Ganesa, Sarasvati and Durga, Krishna, Muruha, Nataraja and Vishnu, and Siva and Rama. One thing however has to be clearly borne in mind. Although we have here the worship and festival for many forms of deities, it does not alter the basic concept of Hinduism; namely that there is only one God without a second. This book thus deals only with the Hindu festivals; Saiva and Vaishnava, besides a large number of non-religious or social festivals. These may of course be general to the whole of India but particular to Tamil Nadu. Unlike the others; Christian and Muslim, these had originated on the Indian soil and belong to India and to Tamilnadu. The families which had converted themselves to the other religions, may yet be found to celebrate some of these festivals like the Tamil New Year Day, Dipavali and Pongal.

It may be remembered that the two religions Jainism and Buddhism had some currency in Tamilnadu for a few centuries in the first millennium after Christ. Of the two religions, Jainism fad been the state religion for some time at Madurai the Pandiya capital and at Kanchi the Pallava capital. Because of this position that religion had been able to contribute to a slight extent to the art and culture of the period. The contribution to art took the form of sculpture, architecture and painting. But the Digambara Jainism in Tamilnadu was a religion which negated life and so possibly, although it had temples and temple festivals on a small scale, it could not have contributed in any appreciable manner to the joy of public life and its rejoicings and festivals, the occasions of rejoicing. Music was virtually taboo in the Jainism of Tamilnadu and women were kept under the thumb, since it was and ineluctable doctrine with the Jains, that women and music are to be put down because they were obstacles to one’s spiritual progress. Therefore though Jainism was the state religion for sometime, it did not leave any mark or have any impact on the life of the Tamil people in general There have been no festivals or rejoicings worth the name that had taken root in society because of the Jains. They might still be a force to reckon with in other part of India., but not in Tamilnad. Hence we do not have anything to say about Jain festivals in Tamilnad.

The same is the case with Buddhism. It was never a state religion here and its mark on Hindu society was much less, We do not therefore have anything to say about the Buddha festivals. However the Indian Union has taken up the birthday of the Vaisaka suddha Poornima, as a national festival an its echoes are certainly heard in Tamilnad.

Among the festivals elaborately dealt with here, under the various, predominate. the Vinayaka, Saiva, Skanda, Sakti festivals can be brought under Saivism, while Krishna and Rama and others like Vaikuntha- Ekadasi and Kaisika Ekadasi will fall under Vaishnavism. Sarasvati, new year day and pongal belong to both. But all this in reality does not detract from the concept of One God in Hinduism. There is only one God without a second. Whatever is said in the various names as Ganapati, Muruha, Durga, Vishnu, Krishna, Nataraja, Surya or Siva – all goes to the One Supreme, of which these are all well understood to be simply manifest forms.

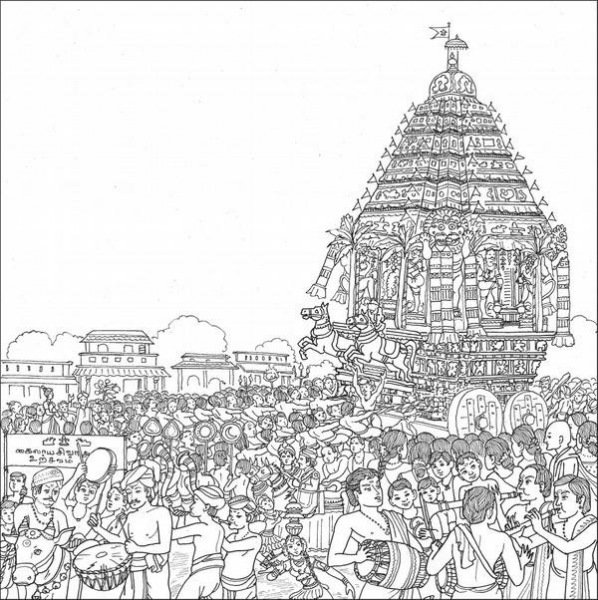

There is a continuity in the festival celebrations and the festival culture of Tamilnadu which is hardly to be found elsewhere. Several factors have contributed to this continuity. The chief factor is the large number of temples which stud the country. Even small villages have large temples to Siva and Vishnu. All the temple festivals involve the entire society around, through daily aradhana, procession, music particularly the nagasvaram, singing of devotional songs, distribution of prasadams etc. The second factor is that foreign religions had not held any great sway over the Tamilnad. There was Jain rule in Madurai for some centuries which, historians call the dark age in Pandinad. Again there was also Muslim rule there for a short period of about half a century. But Cholanad, which was the custodian of the culture of the land, was ruled continuously by Hindu rulers. After the Cholas, the Vijayanagar empire, then the Nayaka the Mahrattas, Till the last Mahratta ruler gave up his land to the British. Then was no foreign religious oppression and this was an important factor in the continuity of the festivals.

Besides, the songs of the Nayanmar and the Alvar in the temples was another integrating force of permanence. All these contributed to the retention of the great culture unbroken.

Modern scientific advance has added a new dimension to the celebration of festivals and that is the abolition of distance. Means of communication like the radio, television and the news paper take u9 to festival centres in no time or bring the festivals to our very doors. Distance is thus bridged and we are given the means of understanding others in different climes and places.

Opportunities for understanding and for spreading peace and goodwill have been brought to one’s own doors and this is sure to result ultimately in the full realisation of the bard of two thousand years ago who declared ‘that the whole world is kin and any place is my place.’